Beacon Machine Manufacturing Co.,ltd

The Heartbeat of Precision: Why the BIP Signal is Critical in Diesel Common Rail Systems

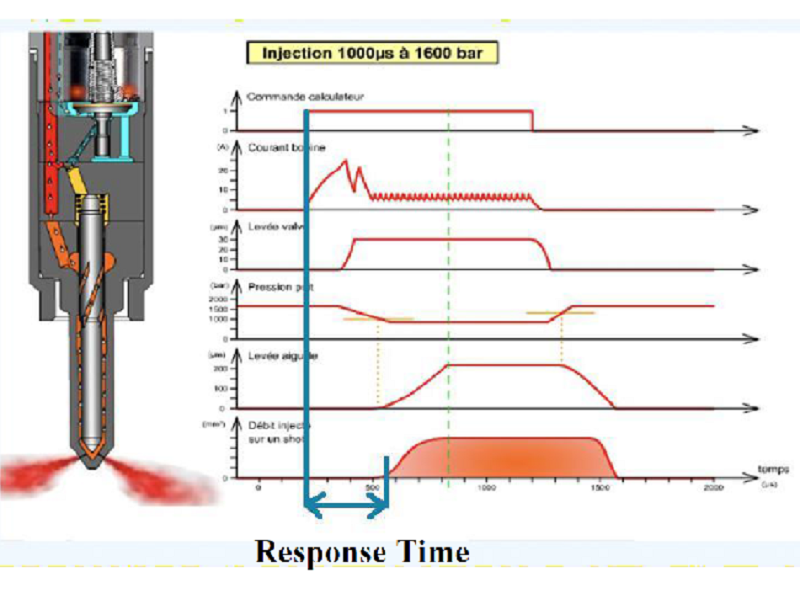

In the world of modern diesel fuel injection, milliseconds matter. The difference between a smooth-running engine and one that knocks or emits black smoke lies in the precision of fuel delivery. At the center of this precision is a specific diagnostic parameter known as BIP (Beginning of Injection Period).

While the ECU (Engine Control Unit) sends a command to inject fuel, the BIP signal confirms when the injector actually responds. This article explores the physics behind BIP and why it is the "Holy Grail" of injector calibration and diagnostics.

1. What is the BIP Signal?

BIP stands for Beginning of Injection Period. It is an electrical feedback signal detected by the ECU that indicates the exact moment the solenoid valve within the injector has mechanically closed.

In Solenoid-controlled Common Rail injectors (and EUI/EUP systems), fuel pressure cannot build up in the nozzle until the spill valve (or control valve) is fully closed. Therefore, the BIP marks the actual start of the hydraulic pressurization phase, not just the start of the electrical current.

2. The Physics: How is BIP Generated?

To understand BIP, one must understand the interaction between electricity and magnetism.

-

Energizing: The ECU sends a high voltage (often 48V-80V) to the injector solenoid to create a magnetic field.

-

Movement: The magnetic force pulls the valve needle or armature against a spring.

-

The Impact (BIP): When the valve hits its seat (closes), it comes to an abrupt stop. This sudden stop changes the magnetic flux within the coil. According to Faraday’s Law of Induction, a change in magnetic flux induces a voltage (Back-EMF).

-

Detection: This induced voltage causes a momentary ripple or change in the slope of the current flowing through the circuit. The ECU detects this ripple. That ripple is the BIP signal.

3. Why is BIP "Mission Critical"?

If the ECU knows when it sent the signal, why does it need the BIP feedback?

A. Correcting Mechanical Lag (Latency)

There is always a delay between the ECU sending the electrical pulse and the valve actually closing. This is called electro-mechanical lag.

-

Without BIP: The ECU assumes the lag is constant.

-

With BIP: The ECU measures the exact lag. If the valve is sticky due to varnish or cold oil, the BIP signal arrives later. The ECU then extends the energizing time to ensure the correct volume of fuel is injected.

B. Precise Fuel Metering (Quantity Control)

In modern Euro 5 and Euro 6 engines, Pilot Injections (pre-injections) are incredibly small—sometimes less than 1.0 mg of fuel.

If the valve closing point (BIP) shifts by even 20 microseconds, the fuel quantity could change by 50%, leading to engine knocking (too much fuel) or misfire (too little fuel). The BIP signal allows the ECU to adjust the "End of Injection" to maintain perfect quantity.

C. Wear Compensation (Adaptation)

As an injector ages, the internal spring weakens, and the valve seat wears down. This changes the travel distance of the solenoid.

-

The Solution: The ECU monitors the BIP drift over the life of the engine. It learns the new characteristics of the aging injector and applies offset values (Adaptation Data) to keep the engine running smoothly.

4. Diagnostics: Interpreting BIP Failures

For technicians using test benches (like Hartridge or Bosch equipment), the BIP value is a primary health indicator.

-

BIP Too Large (Late): Indicates a sluggish solenoid, high electrical resistance, or a "sticky" valve due to contamination.

-

BIP Too Small (Early): Indicates a weakened return spring or incorrect air-gap setting inside the solenoid.

-

No BIP Detected: The valve is not moving, or the solenoid is open/short-circuited.

Conclusion

The BIP signal is not just a data point; it is the bridge between the digital commands of the ECU and the mechanical reality of the fuel injector. By monitoring the exact moment the solenoid valve closes, the system ensures that emission standards, power output, and fuel economy are maintained throughout the vehicle's lifespan.

Related products

Language

Language